Modernity and urbanisation has led to the decline of traditional form of clothing, however the saree continues to remain an eternal favourite. While means of production, style of draping, and designs, may have changed markedly over times, one factor remains unchanged: the love for sarees among Indian women.

From a fragment of cotton found on a metal tool in Mohenjo-daro, and silk found in ornaments excavated from Harappa and Chanhu-daro, to the modern synthetic fabrics, mankind’s journey in the arena of textile has been long and colourful. In ancient India, both stitched and unstitched lengths of fabrics, such as cotton and silk, were draped around the body and formed the main garments. While the men wore a turban on their heads, tied a piece of cloth around their waists (similar to a dhoti), and placed a shawl like cloth around their shoulders, the women too draped a cloth around their waists, and sometimes covered their upper torso with a blouse, a tunic, or an odhni / dupatta like cloth. These garments draped perfectly, were made keeping the climate in mind, and catered to the trends and tastes of the time. One look at a woman’s garments and style, and you could guess her caste, marital status, area of origin , and her social standing.

Ajanta frescoes showing women in drapes covering the upper torso and the lower antariya. Picture source – Wikipedia.

A donor couple – The man is wearing a turban and the antiriya. The woman is wearing a garment that drapes around the waist and below, leaving her upper torso uncovered. Shunga period, 2nd c. BCE, Haryana. National Museum, New Delhi

Left – A saree like garment with perfect drapes framing a woman, Mathura, 2nd c. CE (Picture source Wikipedia). Right – Devi Yamuna ( Gupta period, 5th c. CE, UP) in a saree like garment that drapes from waist down below, and covers her upper torso, and the aanchal is wound around her arm, National Museum, New Delhi. Notice how both the women are seen wearing a waist band.

A Matrika figure from Gupta period, 6th c. CE, seen wearing a blouse, while a pleat on her waist shows a garment that would drape below. National Museum, New Delhi.

The word sari/saree is a derivative of the Prakrit word śāḍī, with the original term being the Sanskrit word śāṭī meaning “a piece of cloth”. It is likely that the petticoat and blouse, two necessary accompaniments of a saree in modern India, were later additions during the colonial era.

Draping a saree – Bengali Style

Draping a saree to accentuate one’s figure is an art by itself. There are innumerable references to it in ancient Indian literature like satavallika or pleats with many fine folds, or hastisaundaka or pleats that resemble an elephant, abound in Buddhist literature. It is evident that in the ancient times it was customary to tie a piece of cloth around the waist, and sometimes a cloth would also be draped over the head and upper torso. The uttariya that was used like a shawl over the shoulders can be drawn parallel with the modern odhni, while the stanapatta or kanchuli likely formed the choli or blouse. It is conjectured that the lower garment, which was known as antariya, and the upper uttariya fused sometime between 2nd c. BCE and 1st c. CE to form a long strip of cloth or śāḍī. The long aanchal or pallu of the saree, which hangs free after draping over the shoulder, was used for covering the head.

The intermediary form of draping a saree, which was shorter in length and worn without a blouse or a petticoat, was prevalent in Bengal until some years ago. It was known as the aatpoure form of draping, and many of us have seen our grandmothers wear saree that way. While aatpoure still remains in fashion during festivities and is a favourite of Bollywood movies when portraying a Bengali woman, it is now worn with a blouse and petticoat.

A picture postcard of a Kalighat painting from the 1900s depicting a woman with her saree draped in the aatpoure way, without a blouse or a petticoat. The saree goes anticlockwise first around the waist, followed by a second drape in the clockwise direction. The loosely hanging pallu is then placed over the shoulder, and can be easily draped over the head when in front of strangers or when required as per customs. At the end of the pallu, tied in a knot, from one corner of it would hang the various keys of the household. During those times when women remained within the four walls of the andarmahal, the keys hanging from the aanchal (pallu) were the symbols of power, denoting supreme control of the woman over her house and household matters as the Grihini. The keys of the larder (bha(n)rar gharer chabi) and almirah keys were deemed the most powerful ones.

During the mid 19th c. CE when women empowerment slowly started taking shape,

Jnanadanandini devi, sister in law of Rabindranath Tagore, was the first among Bengali women to move out of her in-laws’ home, defy the purdah system, and travel to Bombay to live with her husband who was posted there as the first Indian member of the Civil Services. It was she who first developed the new style of combining the saree with a blouse and petticoat, to enable women move out of their seclusion in the andarmahal and take part in outdoor activities. She achieved this by fusing the Parsi and Bengali style. While adopting the Parsi jacket and petticoat, she kept the Bengali style of wearing the pallu on her left shoulder. This style, which lacked the pleats from the waist downward, became popular among the Brahmo Ladies. Jnanadanandini devi, a social reformer and an advocate of woman empowerment, gave classes to women willing to learn the new way of draping the saree.

Three generation of women from the same family in their distinct style of sarees. Top left – Maharani Suniti Devi of Coochbehar. She was the daughter of Keshab Chandra Sen, one of the founding members of Brahmo Samaj in Bengal. The Brahmo Samaj ushered in a new era in women’s freedom and allowed them to appear in public. Suniti devi, here, is seen wearing the attire often chosen by Brahmo women when they appeared in public, with the pallu in front, a full sleeved jacket worn as blouse, and a laced cloth to cover the head. On her right is her daughter-in-law Maharani Indira Devi. Indira devi was widowed at a young age, and she followed the Bengali custom of wearing only white sarees after the husband’s death. However, she moved away from the tradition of wearing only white “thaan” sarees (cotton or mulmul), to wearing customised chiffon sarees in white with zari/silk borders. This soon caught the fancy of the entire nation, and chiffon sarees became the order of the day, both among royalty and commoners. Bottom – Suniti Devi’s grand daughter Maharani Gayatri devi, is wearing the saree in the modern form with pleats from waist below, and without the customary head cover, unlike her grandmother and mother.

The modern style of wearing a saree was derived from mixing the style pioneered by Jnandanandini devi with the Nivi style of Andhra Pradesh. In this style, the saree is draped by first tucking one end into the waistband of the petticoat and then wrapping the cloth around the lower part of the body once, followed by hand-made even pleats that are tucked into the waistband, around the navel. After one more turn the loose end is then draped over the left shoulder. Seen on right is Maharani Ourmilla Devi of Jubbal wearing saree in the modern style.

style pioneered by Jnandanandini devi with the Nivi style of Andhra Pradesh. In this style, the saree is draped by first tucking one end into the waistband of the petticoat and then wrapping the cloth around the lower part of the body once, followed by hand-made even pleats that are tucked into the waistband, around the navel. After one more turn the loose end is then draped over the left shoulder. Seen on right is Maharani Ourmilla Devi of Jubbal wearing saree in the modern style.

Bengali Sarees

Jamdani: The word Jamdani is a Persian derivative and denotes the floral designs that adorn these sarees. There are four types of jamdaani: Dhakai, Tangail, Shantipuri, and Dhaniakhali. Jaamdani was woven on fine muslin, a material also known as abrawn (running water) because when it was placed under running water, the fine muslin would turn almost invisible. Alternatively it was also known as shabnam (evening dew) and bafta bana (like a cloud). Muslin finds mention in various travel accounts of the Chinese, Arabic, and Italian traders, along with Arthashastra, as a fine cloth from Pundra and Bangla.

Making a Jamdani saree is extremely time consuming, and requires intense concentration and hard-work. It is hand woven on a loom by weavers that “place the patterns, drawn upon paper, below the warp, and range along the track of the woof a number of cut threads equal to the design intended to be made; and then, with two small fine-pointed bamboo sticks, try to draw each of these threads between as many threads of the warp as many may be formed. the shuttle is then passed through the shed” (Taylor James, Descriptive and Historical account of the Cotton Manufacturers in Dacca, 1851. cited in Geroge Watt, p. 281).

In Jamdani, the cotton fabric is woven with cotton or zari threads and the sarees have two to four large motifs (mango motifs, known as kolkaa) at the junction of pallu and the border. The body of the saree has butis or small flowers. Often a butidar saree with close set butis would be known has Hazarbuti (thousands of butis), or in case of floral motifs which are connected together as in a jewel like setting it would be known as Pannahazar (thousand emeralds). Floral motifs arranged in straight lines are known as Fulwar, but when arranged in a diagonal line it becomes Tersa. Sarees that were dyed a deep indigo with designs in a lighter shade are termed as Neelambari (blue sky).

Hazarbuti and Pannahazar Dhakai Jamdaani sarees. These sarees are woven on an unbleached cotton base while the design is woven with bleached cotton threads, so that there is a light-and-shade effect.

Dhakai Jamdani sarees in modern designs for the highly competitive market of today (Picture courtesy: Gency Chaudhury)

Baluchari:

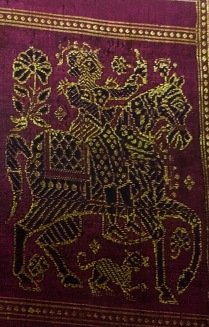

Murshidabad in Bengal is well-known for its fine silk, which is light and easy to drape. Silk weaving in this region started during the early 18th c. CE and flourished under the British patronage. During the Mughal period, Nawab Murshid Quli Khan moved his capital from Dhaka to a place known as Baluchar, on the eastern bank of the Ganga river. Along with the Nawab came many weavers, and the famous Baluchari weave was born when silk was used instead of the gold and silver threads for weaving patterns. Baluchari sarees came with a long pallu that had distinct kolkaas (mango motifs) surrounded by themes that varied from showcasing the lives of nawabs, to railway carriages, Europeans and Indians sitting and smoking hookahs or reading books, amorous couples, dancers, animals, and also scenes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Baluchari sarees focused on reflecting the sociopolitical images of the time, and we see them in the earlier colonial motifs, and later in the nationalist ones where Vande Mataram is woven repeatedly all around in pallus and borders. The basic colour of the sarees were either maroon or purple and the saree bodies had butis all over. In 19th c. CE, flooding of the region by the river Ganga resulted in Baluchari weavers shifting and setting up shop in Bishnupur (Bankura district of Bengal).

Baluchari sarees on Murshidabad silk with their butis and human motifs (here there are two dancing figures)

Baluchari on Murshidabad silk showing an amorous couple and a traditional motif

Baluchari on Mushidabad silk – the weave depicts episodes from Ramayana (Picture courtesy – Gency Chaudhury)

A typical Baluchari pallu with silk weaves showing the kolkaa (mango) motifs

Left: woven theme of a Baluchari saree showing an European riding his horse and his dog going with him. Right: Baluchari saree from the nationalism era, where the word Vande Mataram has been woven on the saree border

Kantha:

Kanthas started as small pieces, usually in square or rectangles, that were made from old torn pieces of clothes, such as dhotis or sarees. The salvaged parts were quilted together and threads dyed in indigo and madder were used for sewing fine embroidery, known as Kantha. Every piece of a Kantha cloth, used either for domestic needs or given as a gift especially for a newborn baby to lie on, would show thousands of running, darning, herringbone and chain-stitch patterns. The patterns on kantha vary from human and animal figures to floral motifs, cars and trains, to fine ornamental patterns. Kantha work in Bengal has always been women oriented work, and it would involve women of the household sitting with their needles, in their long free afternoons, and weaving patterns that often told tales of their yearnings, dreams, aspirations, love, sadness, and heartbreaks. Once the weave of the women from poor households, the same kantha stitch is now patterned on silk sarees and is held dear by those that wear them.

Traditional Kantha patterns woven on silk

Modern patterns of Kantha work on silk (Picture courtesy: Gency Choudhary)

Besides these famous weaves, Bengal specialises in both silk and cotton sarees with prints and simple weaves. These are light and comfortable sarees for those sultry summers of Bengal.

Colourful prints on the light Murshidabad silk

Butidaar taant sarees (cotton weave and base with golden zari on the grey one) Pictures courtesy: Gency Chaudhury

Traditional motifs on plain taant cotton sarees. Lightweight and easy to drape these sarees are a comfort wear during the humid summer months.

(This article was published on Virasat E Hind )